secretes new shell material faster on one side than the other, causing the shell to grow in a spiral. The rates at which shell material is secreted at different points around the opening are presumably determined by details of the anatomy of the animal. And it turns out that—much as we saw in the case of branching structures earlier in this section—even fairly small changes in such rates can have quite dramatic effects on the overall shape of the shell.

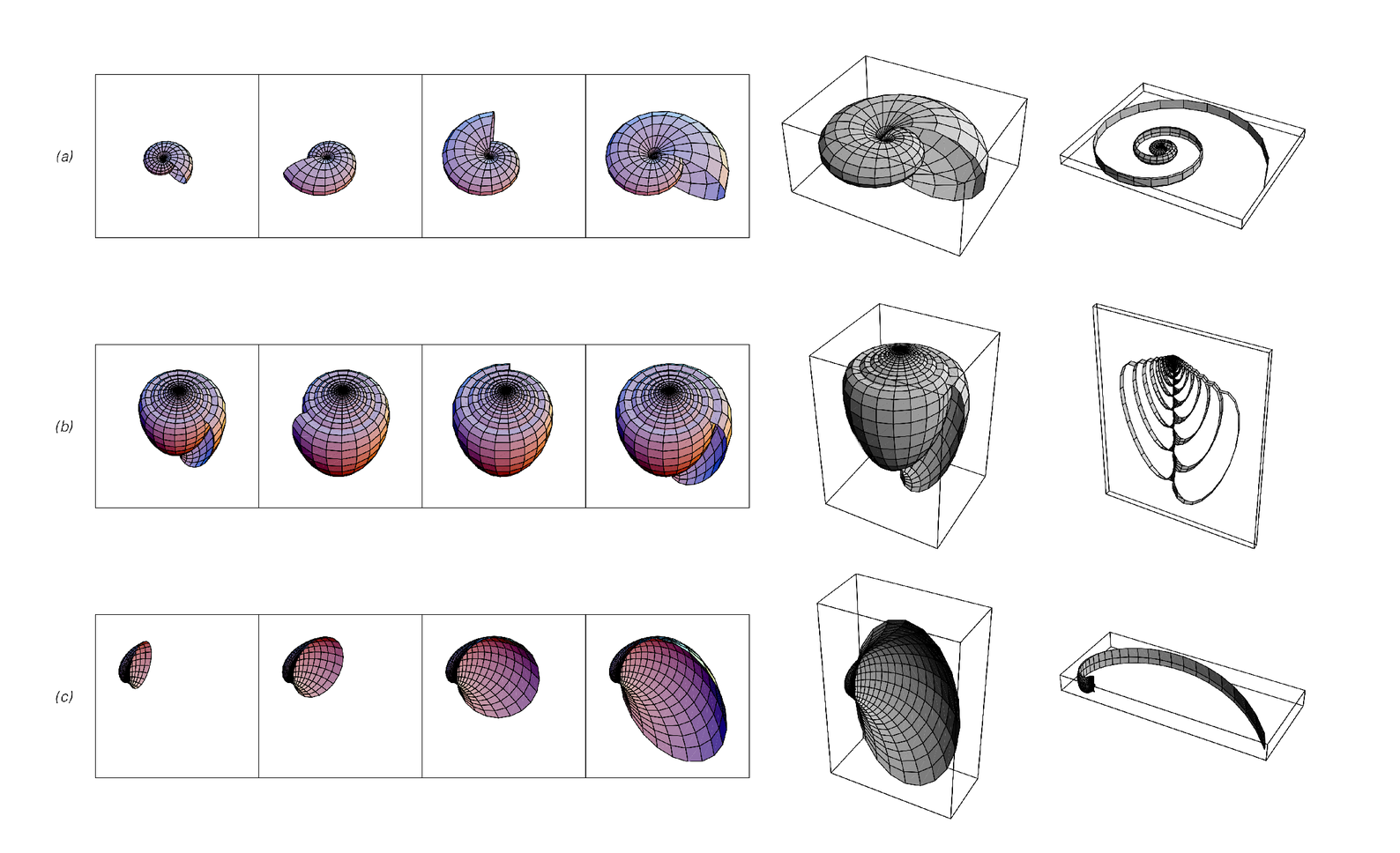

The pictures below show three examples of what can happen, while the facing page shows the effects of systematically varying certain growth rates. And what one sees is that even though the same very simple underlying model is used, there are all sorts of visually very different geometrical forms that can nevertheless be produced.

A simple model for the growth of mollusc shells. In each case new shell material is progressively added at the open end of the shell. The rule on the left shows the amount of material added at each stage at different points around the opening; the line from the center indicates the progressive lateral displacement of the opening. Case (a) is typical of a nautilus shell, (b) of a cone shell and (c) of one-half of a clam shell. All shells produced by adding material according to fixed rules of the kind shown here have the property that throughout their growth they maintain the same overall shape.